Yaniewicz's Story

Recent research has uncovered the remarkable story of Yaniewicz’s musical career and how he came to settle in Britain.

Born in Vilnius (then part of the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth), Feliks Janiewicz began his career as a violinist in the Polish Royal Chapel. Impressed with the young player’s brilliance, King Stanisław August Poniatowski (right) arranged for him to travel to Vienna where he met Haydn and Mozart. When Mozart heard Janiewicz play the violin, he was greatly impressed; Otto Jahn in his Life of Mozart considered that his lost Andante in A major K.470 may have been composed for Janiewicz.

Recent research has uncovered the remarkable story of Yaniewicz’s musical career and how he came to settle in Britain.

Born in Vilnius (then part of the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth), Feliks Janiewicz began his career as a violinist in the Polish Royal Chapel. Impressed with the young player’s brilliance, King Stanisław August Poniatowski (right) arranged for him to travel to Vienna where he met Haydn and Mozart. When Mozart heard Janiewicz play the violin, he was greatly impressed; Otto Jahn in his Life of Mozart considered that his lost Andante in A major K.470 may have been composed for Janiewicz.

Michael Kelly, a famous tenor of the time, wrote that while in Vienna he was privileged to hear two of the foremost performers on the violin in the world, one of them being Janiewicz,‘a very young man, in the service of the King of Poland; he touched the instrument with thrilling effect, and was an excellent leader of an orchestra. His concertos always finished with some pretty Polonaise air; his variations were truly beautiful.’

Janiewicz subsequently travelled to Italy and from there to Paris, where he made his debut on 23 December 1787, performing on the violin at the Concert Spirituel. A mid-nineteenth century encyclopaedia of music evokes the political upheavals which interrupted the rise of his career in France: ‘Whilst in Paris, where he was particularly noticed by several members of the royal family, the French revolution broke out, and soon after the sun of Polish liberty set, perhaps forever. Amidst the tempest of political commotion which involved the ruin of Stanislaus and the dismantlement of Poland, Janiewicz's fortunes were involved in the general wreck.’ He fled to Britain, where he would spend the rest of his life.

Janiewicz subsequently travelled to Italy and from there to Paris, where he made his debut on 23 December 1787, performing on the violin at the Concert Spirituel. A mid-nineteenth century encyclopaedia of music evokes the political upheavals which interrupted the rise of his career in France: ‘Whilst in Paris, where he was particularly noticed by several members of the royal family, the French revolution broke out, and soon after the sun of Polish liberty set, perhaps forever. Amidst the tempest of political commotion which involved the ruin of Stanislaus and the dismantlement of Poland, Janiewicz's fortunes were involved in the general wreck.’ He fled to Britain, where he would spend the rest of his life.

In London he played in Salomon’s orchestra conducted by Haydn, and towards the end of Haydn’s first visit to London played solo concertos at the Hanover Square Rooms in 1792.

Performing in Bath later that year, he was hailed as ‘the celebrated Mr Yaniewicz’ and now spelling his name (hitherto Janiewicz or, on a visiting card which survived as far as a family inventory dated 1925, ‘Janowicz, Count Felicien Stadwici’) with the anglicised Y which he adopted for the rest of his life.

Performing in Bath later that year, he was hailed as ‘the celebrated Mr Yaniewicz’ and now spelling his name (hitherto Janiewicz or, on a visiting card which survived as far as a family inventory dated 1925, ‘Janowicz, Count Felicien Stadwici’) with the anglicised Y which he adopted for the rest of his life.

Yaniewicz moved to Liverpool – by then a fashionable metropolis built on wealth from the slave trade – where he met and married Miss Eliza Breeze in 1799. He was described in the Monthly Mirror in March 1800 as a man who ‘combined the utile with the dolce. He is married at Liverpool; leads the concerts; and is (à la Liverpool) a man of business.’

In 1801 he opened a warehouse for musical instruments in Lord Street, which was to become one of two premises for his business (the other in London), in partnerships with John Green and a London pianoforte maker, Thomas Loud.

By the time these partnerships were dissolved and Yaniewicz setting up new premises of his own, an advertisement in January 1812 announced ‘New Music Rooms and Piano-forte Warehouse in Lord Street, LIVERPOOL’: ‘an entirely new assortment of grand and square pianos… including Clementi & Co, Broadwood, Stodart, Tomkinson etc with upwards of 50 on sale at any time…’ testifying to a sizeable business operation. His final partnership was with a flautist, Gaspard Weiss, who ran the Liverpool operation until it was finally dissolved in 1817.

Yaniewicz’s London base was in Leicester Square, where in 1810 he used a subscription concert series to promote his business and court wealthy patrons: instruments for sale were to be played by ‘first professors’, while his house offered ‘suitable and spacious apartments for the Nobility and Gentry who may honour him with their patronage’. In 1813, he was a founder member of the Philharmonic Society; predating London’s first permanent orchestras, it brought together thirty prominent musicians endeavouring to cooperate rather than compete on London’s busy musical scene, and represented a pivotal moment in the development of the profession and the transition from the patronage system to musical meritocracy. A notable concert in 1814 saw Yaniewicz mounting the first British performance of Beethoven’s oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives.

In 1801 he opened a warehouse for musical instruments in Lord Street, which was to become one of two premises for his business (the other in London), in partnerships with John Green and a London pianoforte maker, Thomas Loud.

By the time these partnerships were dissolved and Yaniewicz setting up new premises of his own, an advertisement in January 1812 announced ‘New Music Rooms and Piano-forte Warehouse in Lord Street, LIVERPOOL’: ‘an entirely new assortment of grand and square pianos… including Clementi & Co, Broadwood, Stodart, Tomkinson etc with upwards of 50 on sale at any time…’ testifying to a sizeable business operation. His final partnership was with a flautist, Gaspard Weiss, who ran the Liverpool operation until it was finally dissolved in 1817.

Yaniewicz’s London base was in Leicester Square, where in 1810 he used a subscription concert series to promote his business and court wealthy patrons: instruments for sale were to be played by ‘first professors’, while his house offered ‘suitable and spacious apartments for the Nobility and Gentry who may honour him with their patronage’. In 1813, he was a founder member of the Philharmonic Society; predating London’s first permanent orchestras, it brought together thirty prominent musicians endeavouring to cooperate rather than compete on London’s busy musical scene, and represented a pivotal moment in the development of the profession and the transition from the patronage system to musical meritocracy. A notable concert in 1814 saw Yaniewicz mounting the first British performance of Beethoven’s oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives.

Yaniewicz had begun performing in Edinburgh in 1804, in the subscription concerts organised by Domenico Corri (an Italian who had moved in 1771 to Edinburgh to direct the concerts of the Edinburgh Musical Society in the new St Cecilia's Hall). His performance in a benefit concert in Corri's Rooms in 1804 was hailed by an enthusiastic reviewer as ‘a perfect masterpiece of the art. In fire, spirit, elegance and finish, Mr Yaniewicz’s violin concerto cannot be excelled by any performance in Europe’.

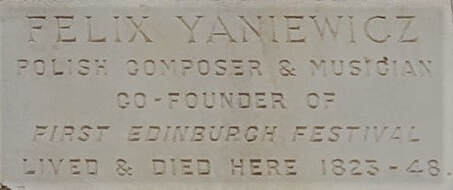

In 1815 he moved to Edinburgh, and co-founded the first Edinburgh Festival which took place in October and November, with an impressive list of aristocratic patrons. Yaniewicz led the orchestra in an ambitious programme featuring Haydn’s Creation, Handel’s Messiah, and symphonies and concertos by Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. After Corri’s retirement in 1816 he became Edinburgh’s chief concert promoter, instituting a series of morning concerts of chamber music for the leisured upper classes ‘attended by a numerous and fashionable audience’.

In 1815 he moved to Edinburgh, and co-founded the first Edinburgh Festival which took place in October and November, with an impressive list of aristocratic patrons. Yaniewicz led the orchestra in an ambitious programme featuring Haydn’s Creation, Handel’s Messiah, and symphonies and concertos by Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. After Corri’s retirement in 1816 he became Edinburgh’s chief concert promoter, instituting a series of morning concerts of chamber music for the leisured upper classes ‘attended by a numerous and fashionable audience’.

Around 1845, his violins were sold, perhaps to clear remaining debts from his musical enterprises (a surviving letter written from Bath in 1822 gives an insight into the financial risks associated with his operations as an impresario, negotiating subscription ticket prices for a concert series in the hope of covering the expenses of the great Mme Catalani, a famous soprano of the day who commanded enormous fees).

The violins are mentioned in a family inventory of 1925, drawn up by Yaniewicz’s grandson, the architect Charles Harrison Townsend. An entry on the inlaid double violin case, which survived in his possession, recounts the story: ‘His Strad he sold for £60, about 1845. See his own letter on the subject… This violin was (so says the violin-expert A Hill of Bond Street – who knows it well) a celebrated instrument, and is now in the possession of a New York collector, well known to Hill. His Amati was raffled for, and produced, 40 guineas!’ The instruments have yet to be traced, but it is intriguing to wonder who is now playing the violins that thrilled Yaniewicz’s audiences two centuries ago.

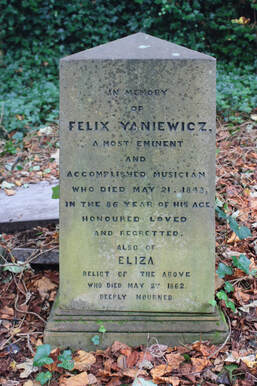

His wife Eliza survived him by 14 years; a headstone in Warriston Cemetery marks their double grave with the inscription ‘In memory of Felix Yaniewicz, a most eminent and accomplished musician, who died May 21 1848 in the 86 year of his age, honoured, loved and regretted. Also of Eliza, relict of the above, who died May 2nd 1862, deeply mourned.’

Of the three children who survived beyond childhood, their daughters Felicia and Pauline were both musicians, while their son Felix became a dental surgeon and pioneered the use of ether as an anaesthetic. Felicia was a pianist and teacher; her sister Pauline a pianist and harpist, who married the Liverpool solicitor Jackson Townsend. Their children included the architect Charles Harrison Townsend, the musicologist Pauline D Townsend (who translated Otto Jahn’s 3 volume Life of Mozart and wrote a biography of Haydn), and Walter Townsend, from whom Yaniewicz’s remaining family in Britain is descended. Music remains a strong tradition in the family; perhaps inspired by her great-great-grandfather, Pat Harrison (1905-1998) founded the Little Missenden Festival in 1960, while her daughter Ailsa Dixon (1932-2017) was a music teacher and composer.

The violins are mentioned in a family inventory of 1925, drawn up by Yaniewicz’s grandson, the architect Charles Harrison Townsend. An entry on the inlaid double violin case, which survived in his possession, recounts the story: ‘His Strad he sold for £60, about 1845. See his own letter on the subject… This violin was (so says the violin-expert A Hill of Bond Street – who knows it well) a celebrated instrument, and is now in the possession of a New York collector, well known to Hill. His Amati was raffled for, and produced, 40 guineas!’ The instruments have yet to be traced, but it is intriguing to wonder who is now playing the violins that thrilled Yaniewicz’s audiences two centuries ago.

His wife Eliza survived him by 14 years; a headstone in Warriston Cemetery marks their double grave with the inscription ‘In memory of Felix Yaniewicz, a most eminent and accomplished musician, who died May 21 1848 in the 86 year of his age, honoured, loved and regretted. Also of Eliza, relict of the above, who died May 2nd 1862, deeply mourned.’

Of the three children who survived beyond childhood, their daughters Felicia and Pauline were both musicians, while their son Felix became a dental surgeon and pioneered the use of ether as an anaesthetic. Felicia was a pianist and teacher; her sister Pauline a pianist and harpist, who married the Liverpool solicitor Jackson Townsend. Their children included the architect Charles Harrison Townsend, the musicologist Pauline D Townsend (who translated Otto Jahn’s 3 volume Life of Mozart and wrote a biography of Haydn), and Walter Townsend, from whom Yaniewicz’s remaining family in Britain is descended. Music remains a strong tradition in the family; perhaps inspired by her great-great-grandfather, Pat Harrison (1905-1998) founded the Little Missenden Festival in 1960, while her daughter Ailsa Dixon (1932-2017) was a music teacher and composer.